I’m reading The Labyrinth of Solitude and I’m so wrapped up in holding the text steady that I don’t notice when the bus blows past El Lobo. We’re a half mile down the road by the time I stagger to the front and explain in panicked Spanish that I meant to get off, “You know, apenas,” just now. My permanent affect in Spanish is contrition, and I keep apologizing to the driver as I try to mime that he needs to stop the bus. I mumble disculpe and perdóname to sleeping Mexicans on my oh-so-long trip to the back to grab my pack. Off the bus, I huck my gear to the ground and try to take stock. I am immediately covered in ants. I curse and giggle and try to shimmy them down and out of my jeans. I sling all forty pounds of prep onto my back and start down the road towards Lobo.

I am a Peace Corps Volunteer working in the stubby mountains of Mexico’s eastern Sierra Madre, and I am about to celebrate Thanksgiving. I live in Jalpan, the de facto capital of the region, and I’m traveling up into the hills to stay with the two other volunteers that the Peace Corps placed out here. James is tall, gangly, and fiercely blonde. He’s Michigan Dutch, Cortez reincarnate in the way he enchants the dusty campo girls. Danielle is a small and perpetually hungry environmental educator out of New York State. They both live in the mero campo, the real country, in pueblos that Jalpan dwarfs, far away from the Internet and bus-lines that keep me pretty well in touch with the world outside.

As I walk up to the misty intersection that leaves the highway and climbs into the mountains, I realize that—God knows why—I’ve worn a cardigan. Between it and my camera, I’ll look like what the grizzled men in this leg of the Sierra refer to as a mano caída, a fallen hand, letting their wrists go limp as they say it. Transit from here to where my friends live goes by way of improvised taxis and converted pickups, and I try to look at home as I sidle up to the group of drivers.

“Who’s going to Río Verdito?” I ask. One of them raises his hand. “Cuanto?”

“Eighty pesos,” he says, about six-fifty US.

“No manches,” I reply, don’t mess around. He laughs. “I live here,” I say, and light a cigarette for effect.

“Not right here”

“Down the road.” He laughs again. “Quince,” I say. Fifteen, less than a dollar.

“Then you’ll have to wait.” I pass him a cigarette and we talk about where he’s worked in the States. He’s been to pick apples near where I used to live in Michigan, but we don’t know any of the same people. One of those things. When a critical mass of travelers builds up and gets into his truck, he waves me towards the cab, but I beg off and sling my stuff into the bed. The ride is gorgeous and I’d rather not have to navigate small talk.

We climb up into the hills while the fog lifts and peaks and pastures dance into view. It’s a cut-rate Bavaria without the more impressive Alps, long narrow valleys blending into terraced farmland spotted with goats and mongrel zebu cattle. We make it to James’ pueblo without incident, and I’m not sure if I’m excited or afraid. We’ve got a turkey, but it’s not, you know, dead yet. Peace Corps is full of this kind of experience—things you want to say you’ve done but which you’re not so sure you want to do. James’ cabin clings to the hillside far up the valley wall, and I poke around for telltale feathers as I hike the muddy cow-path to his door. His kitchen is always unlocked and when I push inside, he’s just taking a pot of water off for coffee.

We do the slap-and-a-fist bump that passes for a handshake out here. “So uh, where is she?” I ask.

“Penelope? I had to do her yesterday. Didn’t want to lead her on.”

“Was she a hassle?”

“No, sweet bird. Calmer than I thought she’d be when I carried her over in the corn sack.”

“I should’ve told you I was gonna write about it.”

“You want to see her? She’s outside.”

James is an engineer, but he spent most of his time between college and the Peace Corps on organic farms, and him also being from Michigan, it’s not his first time to a turkey shoot.

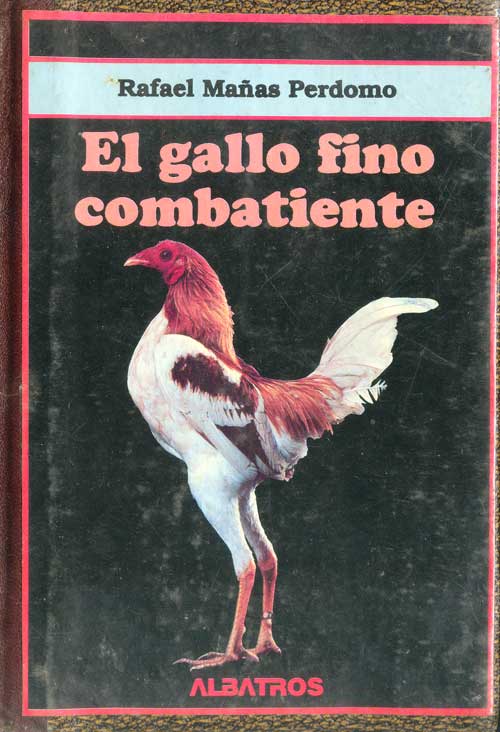

“You use that same handle-less abomination on her?” He only has one knife.

“Yea. Had it so sharp it almost scared me. She went quiet.” He nods over the edge of his porch and I look down to see bloodstains and a mass of feathers in the trees below. “There’d be more down there, but chickens are notorious cannibals,” he says, and indicates the crowd that’s turned out to bawk at us. I look into the pot, and she’s tiny, just enough for four, with little black hairs clinging to the gaping pores where feathers used to be.

“Gross, man,” I say, prodding the little craters.

“Yea. Butterballs, the commercially grown ones, they’re bred to be pluckable. Ugly, all bald and patchy.”

Night’s closing in, so we take the coffee and huddle into his living room to talk. James and I have the best non-native Spanish of our class of volunteers, but we both find it difficult to connect emotionally outside of English, so we talk about the Mitten State for hours when we’re together. It’s not long before we have to bundle up, shaking spiders out of blankets and knit ponchos. It’s as cold as it ever gets up here, not less than thirty five degrees. But Mexico is all poured concrete, and the walls welcome the cold in, making sure that if it’s chilly outside, it’s just as bad in here.

At daybreak, the clouds are gone and the temperature shoots up as we hitchhike to Agua Zarca, where our other volunteer Danielle lives. We catch a ride straight off, and for all that I rip the ashtray out of the car door trying to pull it closed, the guy seems happy for company. He drops us just outside of Danielle’s place, some thirty minutes down the road. When we step out, she calls down from her balcony that there’s no running water, hasn’t been all morning. James and I look at each other. Neither of us has showered much since the cold rolled in, and we’re both pouring sweat now. “Ni modo,” he says, something like ‘Nor a way,’ the national anthem of amiable resignation.

Danielle has to run out to pick up our fourth, Janessa, the other volunteer from down where I live. James visits the neighbors to see if they’ve got water while I unload pie supplies from my backpack. It turns out they have got some, in a rain cistern, and he begins the first of dozens of runs for water, carrying it back in six-liter plastic bottles and dumping it into tubs. Between his frame and the chore, he looks like a broomstick from the Sorceror’s Apprentice scene in Fantasia.

I busy myself with the pies. Danielle hasn’t got bowls, so I make dough in the massive 12-inch cake pans I’ve brought along. Closest I could find to pie tins. James is on a personal crusade against the Coca Cola that’s singlehandedly giving diabetes to rural Mexico, so I’m cutting all refined sugars from the recipes this year. Pecan is easy since honey subs in fine for Karo syrup, but I’m more dubious about the apple. The jar broke in my pack on the way, and I spend much of the time scooping honey out of the bag I wrapped it in.

“You think you’ll have enough water for me to wash anytime soon?” I ask James as he stumbles in puffing from the stairs.

“Screw you,” he laughs, putting his bottles down. I waggle sticky fingers at him. “How’re the pies going?”

“Fucked if I know. I’m going to have to shave some piloncillo for the topping.”

“Good luck with that,” he says, and heads for more water. Piloncillo is solid molasses, boiled and poured into diamond-hard cones. I picked up ten pounds of it on the corner for just under a dollar. I’m willing to do my Mom’s Dutch apple without the sugar, but I don’t feel like I can get away without crumb topping. When Janessa arrives I get her to promise to do me a favor and then leave her scraping a butter knife against the big brown lump.

Janessa’s a middle-height brunette, at turns mothering and full-on partier, and she’s liable to bite your shoulder in times of high excitement. Peace Corps was her dream, and her husband Trey gamely brought his southern Georgia charm down to Mexico along with her. This past October, though, he got the job he’d been waiting for, inspecting operations and developing best practices for California weed farming outfits, and she’s out here alone until he comes down for Christmas.

James and I head out back to consider Penelope. We’ve got a brining recipe written down, but it’s the container that’s holding us up. The pot we brought her over in is too shallow to submerge her, and Danielle’s plastic washtub is larger than her fridge. We’ve heard you’re supposed to keep the bird cool.

“I murdered her, I didn’t nick the bowel, and I’m sure she’s clean.”

“Been out in the sun for a while though.”

“Yea.”

“Weather kind of let us down.”

“It’s a long way from Michigan.” He looks at Penelope. Turns her from side to side. “Wait,” he says, and runs into the house. He comes back with the crisper drawer from the fridge.

“No fucking way,” I say, but he waves me off, and when he lowers her into the plastic, it looks like she’s striking a pose for my camera. Perfect fit. “Maybe that’s what it’s always been for,” I say as we pour salt brine and a table of Danielle’s precious American molasses in with her.

“Guy who invented the refrigerator wondering all his life why we’re putting vegetables in the turkey drawer.”

The pies go into the oven and the girls start on dinner. Pastries aside, we’ve fallen further into gender roles out here, some kind of cultural osmosis. We take out the first bottle of wine. After the luxury of daily Safeway runs, it’s a sweet rarity, way outside of our normal price range for bottom shelf tequila. For this weekend, though, we’ve got four bottles and it feels like a bounty. We’ve got no corkscrew, and I paint most of my shirt a deep violet ramming the cork down.

“Hey, I think there’s eggs in the pasta,” says Janessa. Danielle walks over and looks into the pot.

“And weevils. Could have come in the water, too,” she offers. “You know they eat them here. Some kind of diet.” James nods.

“They say it forms some kind of colony inside of you. You know, in your stomach acid.”

“Protein is protein,” Janessa says, and we all gather round to fish the bugs out with a tiny colander.

Dinner goes well until music starts pouring in the front from the dingy cantina across the way. Banda is hard to listen to in the best of times. Its swaggering imitation of mid-nineties rap values is set to country guitar and a polka bass-line, and when the ridiculous tuba-plus-accordion begins to blare, we shut the door.

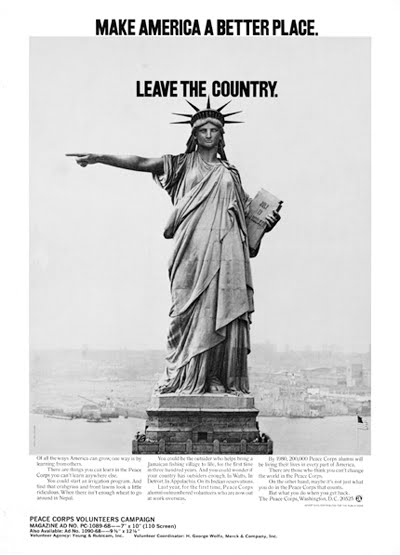

Part of Peace Corps, maybe the only part that matters, is opening yourself to your host country and sharing with it in return. But when we get together for American holidays, we guiltily close ourselves off, trying to create a warm little bubble of home. All weekend we’ll leave huapango and ranchero and even Vicente Fernandez to one side for Macklemore and The Shins, Patsy Cline and the Avett Brothers. I’ll try to start in with Christmas, She & Him and Bing Crosby and Vince Guaraldi playing Charlie Brown, but Danielle will nix it.

“Not until Thanksgiving, and that’s not until Thursday.”

Rules are rules, and as long as we’re pretending that this is the States, we’ve got to respect them. Mexico goes from Día de Muertos on the first of November straight into Christmas, and I walked past the fifty foot iron-and-plastic fir tree in my town square on the first of November with a mix of familiarity and deep confusion.

In the morning, we can’t remember how long we ought to roast a turkey, so we take the campo attitude and wing it, packing her sideways into a stew pot and deciding that three hours or so ought to do it. The dial eschews degrees for an inscrutable I to V range, and we figure that somewhere between II and III is a good bet. The bird safely in the oven, James and Janessa head to the terrace for yoga. We’ve all gotten more New Age since joining up, but Danielle and I draw the line at sugarless pies. She and I turn on Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant,” and sing along to ‘Eight-by-ten color glossy pictures with the circles and arrows and a paragraph on the back of each one.’ We’re together but we’re not together, each of us lost remembering the mothers that first played it for us.

When the chorus comes around, we fall back into the kitchen and yell, ‘Can you imagine fifty people a day, I said fifty people a day walking in, singing a bar of “Alice’s Restaurant” and walking out? And friends they may think it’s a movement,’ before laughing to each other and sighing.

“Time for tequila?”

“Yea.”

When the cooking gets into full swing, it becomes clear that we’ll have far too much food, each of us trying to make all the tastes of home. I’ve got the two pies and a pseudo-casserole of green beans, bacon, and slivered almonds. Slap Chops absent, only dull knives and patience get them thin enough. Janessa’s making cooked carrots and her grandmother’s Jell-O chutney, its myriad fruits replaced by three sad pears and a cup of dusty craisins. Danielle makes stuffing from Bimbo bread, two steps down in substance from Wonder. The most American ingredient is a family-size box of Kraft Mac & Cheese, scrounged at great cost from the Walmart down in the city. We pour it into a baking pan and crumble stuffing over top in lieu of breadcrumbs. It crisps up under Penelope. All of us have given up on the way we smell, and we pack the mashed potatoes with garlic, the white starches yellowing under the onslaught of cloves. For all that we’ve tried to make things as healthy as we preach, we’ve somehow gone through a good twenty sticks of butter before we’re done.

Dishwashing becomes laborious, one of us having to pour from our bottled reserves while another scrubs. Before long, the tub that collects from the basin is full and Danielle starts grilling us on the state of our bowels.

“Somebody take a dump already. We’ve got to flush with the dishwater so I can keep washing.” I go first, and James turns up the music. Danielle’s bathroom is separated from her kitchen by the thinnest plastic and tin—we’re lucky if only the sound makes it through. Shit-shy in the States, I’m not worried. I think it must be true in every country that the first vanity to die in the Peace Corps dies on the toilet. Training is an endless seminar on amoebas and food poisoning, and few meals went by without our speculating on how soon we’d be seeing what we were eating and how it would look when we did. Unwashed vegetables and home-slaughtered turkey long-eaten by time of publication, it looks like we got out scot free this time.

The weather’s still good once Penelope’s out, so we pull Danielle’s small kitchen table outside. The towns here hug the highways as they skirt round the mountains, and when you head to the back of the house, the ground falls away. It’s a five story drop from the edge of her terrace, pine trees rolling out into woodland and a valley that flows as far as you can see. She’s got the best view in all of Mexico, maybe all of Peace Corps, and we use it as the backdrop for a few Last Supper timer photos before we lose patience and fall on the food.

It’s an orgy and we make ourselves sick trying to eat our way back home. By the time we make it to the pies, we’re moaning and cussing with each bite. Only the firmest pain signals from our bellies induce us to quit. We have to stop, and when we do, not even the last three bottles of wine and a good deal of tequila can keep us from seeing what we’ve put off with mad cooking and manic conversation. There’s nothing left to hide that it’s Sunday afternoon and Janessa and I will have to be on the bus back to site at six in the morning. We fall into a melancholy silence, collapsing onto blankets in the last of the sunlight and trying to accommodate our swollen stomachs.

The hills lift the horizon high into the sky, and sunset always comes as a surprise in the Sierra. We were all nodding or napping, and the stars stole out before we knew it, Orion peeking over the hills to our east.

“Do you miss your family?” Janessa asks.

“I dunno. I mean, my folks are in China,” I reply, “So there’s not much of a home for me to go back to for things like this. Plus, you’re married and everything, but for me, every holiday away is a kind of growing-up. Every one a little more adult.”

“You want to be an adult?”

“I don’t feel like one,” I say, but I figure this must be what it’s like for everyone when they’re first out on their own, whether it’s in Mexico or Michigan. Trying to recapture bits of what they’ve left behind.

We stay out until we can’t keep our eyes open, pulling on sweaters and scarves as the wind turns. It rushes around the valley in waves, building to a waterfall roar as it comes to the house and tousles our hair. Dozens of shooting starts streak over us and we put off bedtime, wishing our private wishes.

In the morning, we blow on fingers and chafe our palms together. We pack stuffing and pies into shopping bags and snug them in the spare pockets of our backpacks. We turn and hug Danielle at the door.

“You’ll have to make that apple pie again for Christmas,” she says as we pull away from each other.

And she’s right. I will.